Some of Australia’s best public policy minds met in Brisbane on Tuesday for the Queensland Jobs Growth Summit.

The summit comes at a time when Queensland’s and Australia’s unemployment rate seems stuck at around 6%, about 2% above the lows achieved by the end of phase 1 of the decade-long mining boom (2003-2012), just before the GFC slowdown and the introduction of the Fair Work Act in 2009.

Politicians like to think they create jobs. That is, they think they can create additional employment and lower the unemployment rate either by employing more public servants or investing in new infrastructure.

For instance, Queensland’s Minister for Training and Skills Yvette D’Ath claims there will be a ‘jobs jackpot’ with the ‘job-generating’ Queen’s Wharf development because it “will significantly stimulate the construction, tourism and hospitality sectors and open new markets and opportunities in this great state.”

Similarly, the Palaszczuk Government is: “building or upgrading 17 world-class facilities for the 2018 Commonwealth Games…that will inject $2 billion into the Queensland economy and support around 30,000 jobs.”

Indeed, Premier Palaszczuk last week took her Working Queensland Cabinet Committee to Charters Towers to sniff out “job creating opportunities” that would merit taxpayer support.

This entrenched idea that governments create new jobs by stimulating demand using taxpayer funds is flawed. This is not to say that governments should not invest in worthwhile public infrastructure projects – but the benefits of those investments are higher incomes not more jobs.

Here’s why.

The problem is that, outside of recessions, a lack of demand is not the problem, rather it is bad regulations restraining employment growth that is the problem. This brings us to the most important concept in the jobs debate and what should be the focus of the Queensland jobs summit – the ‘natural rate’ of unemployment.

In 1968, Milton Friedman famously wrote: “At any moment of time, there is some level of unemployment which has the property that it is consistent with equilibrium in the structure of real wage rates.” Friedman went on the say that this “natural rate of unemployment” is determined by the characteristics of the labour markets – i.e. minimum wages, the Fair Work Act, state industrial relations regulations, the efficiency of matching jobs to job seekers, (including the efficiency of transport networks, costs of moving house, and whether we all live in one really big city or whether we live in a demographically dispersed state like Queensland).

Friedman rightly pointed out that many of the labour market characteristics that determine the level of the natural rate of unemployment are “man-made and policy-made” (read: politician-made).

Many studies, including by Australia’s Reserve Bank and the Federal Treasury, have demonstrated Friedman’s proposition. And former Federal Treasury Secretary Ted Evans famously said that Australia’s unemployment rate is a social choice as opposed to an economic choice that we make through the political system.

Recent estimates by both the Federal Treasury and the IMF estimate that Australia’s natural rate of unemployment is 5.75%. The most recent ABS figure has Australia’s current trend rate of unemployment at 5.8%, basically at its lowest possible level outside of a boom. Our economy is growing at the ‘new normal’ post mining-boom/population-boom trend of 2.75%. It is therefore highly likely that any demand stimulus measures governments might undertake will be either a zero sum game or counterproductive.

The IMF has confirmed this view, finding not only that relatively large public sectors coexist with persistently high unemployment (think France), but also that public employment’s impact on private employment is negative.

One large IMF study concludes that: “While in the short-run there might be some gains, in the medium to long-run, public employment may well increase unemployment. Public job creation could cause the destruction of private jobs through, for example, increasing labour taxes or exerting competitive pressure on private producers’ output and wages in the labour market in general. We do not find any evidence that public employment reduces the unemployment rate in the medium to long-run. If anything we found some evidence that creation of public jobs may increase unemployment rate.”

So how are jobs created?

Jobs are created because, as the population grows, demand for goods and services grows, and demand for labour therefore essentially grows in line with population growth.

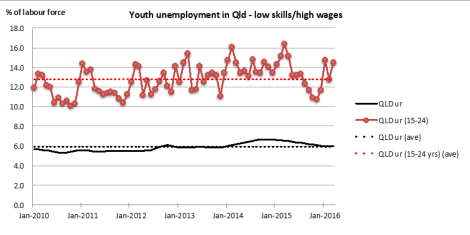

A governments’ proper role, therefore, should be to focus on reducing the natural rate of unemployment, which quite clearly has risen since the introduction of the Fair Work Act in 2009.

The Turnbull Government must reconsider the Fair Work Act in light of the too-high youth unemployment rate. Australia should not tie itself to the mast of a ‘high-wage’ economy, rather we should be an ‘all-wage’ economy where there is a wage for every skill level. Remember, people climb ladders in life if given the opportunity of getting on the first rung. And most often the best way to learn valuable new skills is on the job.

At the state level, the Palaszczuk Government should deregulate retail trading hours, which is surely a no-brainer for a Labor Government focussed on job creation. In addition, Palaszczuk needs to carefully calibrate her regional policies, not overinvesting in thin jobs markets, and not oppose efficient FIFO operations so as not to create ghettos of unemployment in regional centres. We should better appreciate the job matching advantages of the deep and diverse labour market in the south-east of the state.

And, as part of Federation tax reform, state governments need to reduce and ultimately eliminate transaction taxes, most notably stamp duty on housing that restricts labour mobility.

Our ‘jobs’ objective must be to reduce the natural rate of unemployment by 1% from 5.5-6% to between 4.5-5%.

Federal Treasury modelling (and basic common sense) has shown that such a reduction in the natural rate of unemployment is likely to be associated with significantly higher tax revenues and an increase in national saving.

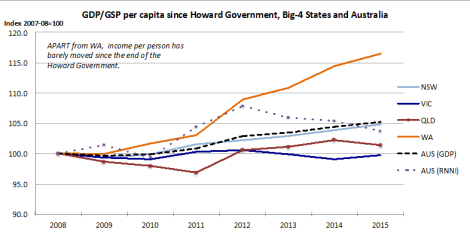

All governments in the Australian Federation must be focussed on the dual goals of lowering the natural rate of unemployment and increasing real income per person. Together, these two measures define the level and distribution of our living standards.

When governments consider new regulations, they should ask: “will this increase or decrease the natural rate of unemployment?” Similarly, when governments consider new spending or taxing policies, they should ask: “will this increase or decrease income per person?”

This is especially the case in relation to multi-billion dollar infrastructure mega-projects like Brisbane’s Cross River Rail. When considering these projects we should not be fooled by the large number of jobs created through the construction phase of projects – these are largely illusory ‘sugar hits’ that cost taxpayers and crowd out private sector activity. The real test of government expenditure is the overall costs and benefits, which not only puts the emphasis on sensible, hard-nose cost-benefit analysis, but very much puts the emphasis on the long-run benefits of projects.