Alan Kohler is one of our best commentators on economics, so it says something about the strength of the establishment view opposed to negative gearing that his piece a week ago in the Australian (Why_the_election_is_a_referendum_on_house_prices) is so riddled with conceptual errors.

It also says something about unreal expectations of the effect the ABCC may have.

His thesis is that the next election will be a referendum on house prices (itself highly unlikely) because both the ALP’s negative gearing policy, and the government’s Australian Building and Construction Commission are aimed at lowering housing costs.

The idea that tax regimes and building costs are the most significant factors governing housing affordability is wrong.

While they can have a significant effect, supply and demand are actually the most important.

If the federal government wants to cure housing affordability then it needs to lean on the states to ease planning restrictions so that more housing can be brought on more quickly.

It also needs to look at restricting the number of migrants coming to Australia, which, apart from the age profile of our population, is the greatest determinant of population growth.

In the twelve months to January, 117,968 dwellings were approved around Australia in the 12 months to September 2015. Over the same period population grew by 313,000. Assuming a household size of 2.6 people per dwelling we needed 120,500 dwellings to be constructed in addition to those needed to replace existing obsolete ones.

Net overseas migration in that period was 167,600, or just more than half the population growth. While less than migration in the recent past, which peaked at 315,000 in December 2008, it is still around the average, and the housing market is still trying to adjust for the close to 2% population growth that Australia has been sustaining in recent years.

Kohler’s thesis is that limiting negative gearing to new housing will lower house prices. It’s certainly what the ALP policy claims although they are now trying to back away from that given the unattractiveness of a fall in property values to home owners. And it’s what the short term economics suggests will happen.

As an aside, the fact Labor appears not to have thought of the consequences of lowering housing prices is because they are attracted to abolishing negative gearing to increase the tax take much more than they are to housing affordability.

But the argument on negative gearing is more complex than that. While abolishing it, if only in part, will disrupt the housing market in the short term, over time it won’t in itself suppress house prices.

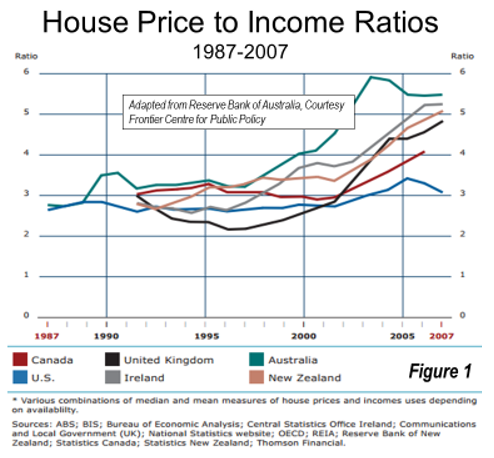

Australia is not particularly out of line with many other rich countries in the world, many of whom treat negative gearing in different ways to us. Demographia compares property prices in a number of countries and markets on the basis of the ratio between median house prices and gross median family income.

Australia’s overall affordability index is 6.4, which is less than New Zealand (9.7) and Hong Kong (19.0). Internally, Australia’s affordability ranges between 2.5 in Karratha, to 12.2 in Sydney.

From the graph below you can see that house prices took off as interest rates retreated from their highs in the 70s and 80s.

Source: 12th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2016 p.7

It’s the mixture of supply and demand, plus the availability and price of credit, that are the strongest drivers of price.

His argument about the ACCB is similarly flawed. While he argues it will cut the cost of building high rise apartments, and that this will flow on to housing, this will be a passing effect.

If it is cheaper to build apartments, then over time developers will be able to bid up the price they pay for sites, given the willingness of the market to pay a given price.

Landowners, not purchasers, will be the biggest beneficiaries.

Indeed, it looks likely that apartment prices will fall in the short term, not because of the ABCC, should it ever arrive, but because of an oversupply. This is particularly true in Brisbane where the state government opportunistically increased the densities on a large number of near city sites, increasing supply, and profitability, without the need to manufacture more land.

The area where the ABCC will have its biggest effect will be on government projects – things like freeways, bridges and tunnels, where land is a very small part of the cost, and construction a significant part.

The reasons for opposing changes to negative gearing have little to do with the long run, and everything to do with maintaining the current integrity and justice of the taxation system, and keeping prices steady in the near run.

There is nothing wrong with offsetting income against costs in the same economic entity. It is not a tax dodge, as Kohler asserts, but the way the tax system works.

If I own two businesses in the same company or trust, one with negative cash flows and the other with positive, then there is no question I can pool my income and my costs and net the two out against each other.

There is no conceptual difference between that and offsetting a loss making business I own in my own name against other income that I earn in my own name. It would be inefficient and unjust not to allow me to pool income and costs just because I own it personally rather than corporately.

Pity the current and future homeowners of Australia when this level of analysis proceeds from one of our best and brightest.