With the release of the December 2019 quarter figures by the ABS we have just released our most recent housing affordability report (to download click here).

Housing affordability in most cities remains within historically comfortable limits, so this month we also looked at one probable effect of the COVID-19 pandemic – mortgage stress.

Our analysis is done on the assumption the economic recession caused by the infection will have run its course within 12 months, and that in the meantime borrowers may actually lose their jobs or be put onto a part-time wage.

In this case many Australians will want to limit their expenditure, and maybe draw on some of their accumulated wealth, until full-time employment returns to them.

How feasible would it be for them to ask their bank for a repayment holiday, and what position would it put them in at the end of that repayment holiday?

This is not just an issue for the borrower, but the lender and the prudential authorities also need to consider their positions.

If the borrower suspends payments for a year, then the unpaid interest would be loaded onto the balance outstanding on the loan at the moment they stopped paying.

This means when they resume payments, if the interest rate is unchanged, then their payments will be higher. It also means, unless there is a lift in the housing market, their security ratio will have deteriorated.

Banks do not normally worry about security ratios as long as the mortgagor is making their payments, but if they stop their payments then the bank may make an assessment of the value of the house in case they need to sell it to recover the debt.

So the security ratio may become important in this situation, particularly under the responsible lending guidelines. This would also extend to repayment ability. The banks may need to exercise some flexibility, as might the regulators, unless they want to see a large number of forced sales.

We worked on the assumption that the worst thing for the Australian economy, on top of the stock market crash, would be a housing market collapse. It’s also something that the banks should want to avoid, given the huge amount of household debt secured against the family home, as well as geared housing investment.

At a later date we will analyse the likelihood of a crash in the housing market, but for the moment we’ve asumed that house repayments are not that different to rent payments for most new homeowners, and that more established homeowners will be even relatively better-off again.

It should be noted that our maths are conservative because our model uses average house prices, an 80% gearing ratio, and does not factor into account drops in interest rates this quarter.

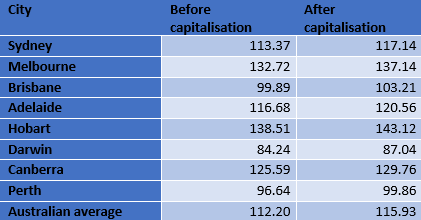

What we found was that if you increased the mortgage by a full year’s worth of interest payments the Australian average index figure rose to 115.93. That still leaves it more affordable than most of the period back to 2003, and almost indistinguishable from the index figure in the December quarter of 1994, 25 years before, of 115.49.

There would be a small blowout in the loan security ratio from 80% to 83%, which is about equal to the real estate commission should the borrower decide to sell the house because they couldn’t afford to keep it.

Of course, this is only an average story. As the table below shows, the best cities to use this strategy in would be Sydney, Brisbane, Darwin and Perth, which are all at historically quite affordable levels.