The Corinna Economics report on paying for a home deposit using superannuation is convenient for the superannuation industry, but deeply flawed.

It is true that any scheme allowing a home buyer to borrow part of the deposit from their superannuation could put upward pressure on house prices by increasing repayment capacity, assuming all other things are equal.

But there are many other factors that put upward pressure on housing prices such as an increase in real wages, a decrease in interest rates, or even an increase in productivity.

It would be bizarre to argue against any of these on the basis that they would affect house prices.

The reality is there are many reasons for house price rises, with 70% of house price increases being attributable directly to falls in interest rates.

The rest is caused by Australia’s massive net inward migration, restrictions on supply which at the moment include planning regulations, red tape, frontloading of infrastructure charges, shortages of manpower and materials caused by competition from government infrastructure projects, and low productivity in the unionised parts of the industry.

Ironically the last is caused by some of the clients of the superannuation firms that commissioned the research.

Pressure from inward migration will continue. This week Education Minister Jason Clare conceded that Australia’s migrant intake remained too high with the Australian Bureau of Statistics predicting the nation’s migrant intake would exceed 400,000 in FY24.

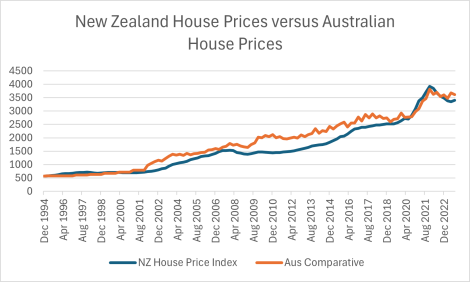

The Corinna Economics analysis claims New Zealand, which allows super to be used for house purchases, proves that the scheme pushes up house prices.

But it is hard to fathom how this could be the case when Australia, which doesn’t have the scheme, has seen prices continue to escalate at a similar rate to New Zealand which does have the scheme.

The analysis also concentrates on income from super in retirement and ignores the cost of renting in retirement, as well as the dramatic increase in net worth that occurs through home ownership.

The greatest indicator of stress in retirement is renting, and people typically have a house worth more than their superannuation balance when they retire (which will be a great benefit under Labor’s new aged care rules where older Australians will need to contribute more).

These two factors mean that a retirement policy that advantages superannuation at the expense of home ownership is not fit for purpose.

There is also confusion in the analysis about the alternative uses of potential home purchasers’ superannuation.

Australia needs a certain number of dwellings to house its population, and this doesn’t vary according to who owns the stock.

At the moment superannuation funds are lobbying the government to give them concessions so they can invest in ‘build to rent’ residential properties to meet the demand for rental properties caused by the decline in home ownership.

If the funds retain the savings of would-be first home purchasers and invest it in housing rather than allowing the beneficiary to do it themselves, then it will be the funds that put upward pressure on house prices, but the pressure will still be there because of the lack of supply.

It is clear the solution to housing affordability is to facilitate more supply and less immigration, with funds liberated from superannuation to ensure that Australians get into their own home faster.

The superannuation industry has to realise that housing is the best form of savings and security for Australians, and returns from super come second.