Speaking for my generation, I “like” this budget. No chance we’ll have to pay for the benefits. The bill is being passed on to the next generation who will have to cope with the debt my generation is generating. Thank goodness there are no parsimonious Presbyterians like Menzies, who paid back Australia’s WWII debt, in the current state government.

The 2018 Queensland budget is in a long tradition of state budgets. It spends money it does not have, raises taxes to only partially pay for its commitments, and has no clear underlying plan.

Jackie Trad inherited more than her seat from Anna Bligh (whose only budget surplus as Treasurer or Premier was the one she inherited from former treasurer Terry Mackenroth) – she appears to be channelling the same economic philosophies.

While Jackie has produced a substantial surplus this year, this ignores a massive spend on infrastructure, to be funded by a 35% increase in state government debt. On the older accounting methods for government budgets, this one would be massively in deficit.

I haven’t had time to do a comprehensive analysis, but here are some observations.

Debt

Annastacia Palaszczuk claimed at the last two state elections that debt would be paid down using the returns from Queensland’s power generation, which she kept in public hands. Even though Jackie Trad brazenly claimed the government had “paid down $17 billion worth of debt in the general government sector”, general government sector liabilities continue to grow, and within three years are expected to increase to $83 billion from the $74 billion they are today.

While talking General Government Sector liabilities gives us a big figure for debt, it has to be conceded that some of the liabilities are for public service superannuation, which is balanced out by an asset pool that is meant to pay for that superannuation. It also takes account of debt owed by the power generators and distributors, which they may have a chance of paying back. Looking at the state government’s on-balance sheet debt gives a clearer picture in some ways of what is happening.

In its last term the government moved some of its own debt onto the power generators, and raided the superannuation fund, to make its on balance sheet debt position look better. That game seems to have played out, so the $9 billion increased borrowings will be added to the government’s own borrowings, taking them from $31.367 billion now to $42.290 billion in 21/22, an increase of 35%.

This is up there with the profligacy of Anna Bligh which led to the privatisation of railways and ports.

Surplus

The government expects a surplus this year of $1.512 billion, “more than three times the size of the Mid-Year Fiscal and Economic Review forecast.” This tells us that treasury is not very good at forecasting coal prices and volumes. It also indicates how volatile the commodities markets can be. I put out a release yesterday pointing out that this surplus should be treated as a windfall and used to pay off debt.

While the surplus has reduced the debt this year, that is only temporary, and net debt in 20/21 is now forecast to be only $300 million lower than it was forecast to be in last year’s budget. Meaning that most of this year’s windfall will have been borrowed again, particularly as taxes will be approximately $2 billion higher over the period than predicted in last year’s budget.

Income

The government has increased taxes by roughly $500 million a year, with an average $325 million pa of that coming from a rubbish levy. It will also increase tax on:

- luxury cars (boosting the incomes of luxury car dealers south of the border);

- overseas purchasers of units (leading to fewer units being built and ultimately higher housing costs);

- the 850 largest land owners (hurting their commercial and retail tenants); and

- online gamblers (leading to the bigger gamblers using intermediaries registered elsewhere to place their bets)

The rubbish levy and increased land tax will ultimately be paid by everyone in the state. Jackie’s solution for that is to take some proportion of the tax paid and rebate it to some group. So most of the waste levy is going to be paid to councils so they don’t pass the increased cost on to ratepayers.

This is a particularly stupid policy. There has been widespread community hysteria about some NSW waste being dumped in Queensland, at the same time as there has been wringing of hands because the Chinese have stopped taking recycled rubbish from Australia. So we can export, but not import?

Ipswich has a lot of coalmines that need to be filled and turned into community infrastructure like parks and playing fields. New South Wales has a lot of fill in the form of rubbish. There was a substantial industry based around that simple reality. Now that industry has been destroyed, the coalmines will remain coalmines, and to stop the rest of us paying more to dump rubbish, the state government is giving most of the money raised to the councils, after deducting handling charges, and also putting one third into recycling schemes that are uneconomic and so need government money just to exist.

The lack of efficiency in this arrangement is staggering, and will lead to destruction of wealth.

Expenses

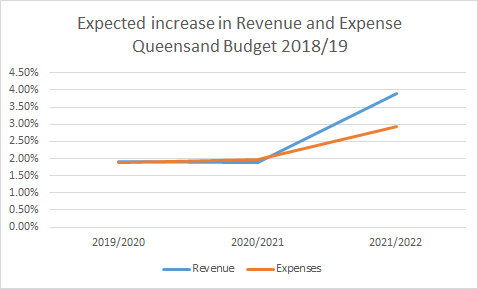

There is moderate growth in expenses for the next two years of around 2%, but then in the third year growth accelerates to 3%. This is more than matched by income, which accelerates by 4% in the same year. This graph shows the relationship between the two.

One expense to watch is Other Interest Expense, which is anticipated to be $1,794,000,000 in 2021/22, which is only marginally higher than for 2016/17, even though the debt on which this is calculated is going to be around one-third higher.

Given that the US Fed raised interest rates by a quarter of a percent yesterday, and interest rates in the markets in which state governments borrow will likely follow suit, this either means that there is a lot of old, high priced debt in the state government’s current portfolio, or the government is being incredibly optimistic about future interest rates. I suspect that expenses will grow by more than what is shown.

Another cause of increase in expenses is the increase in the number of public servants employed and their anticipated pay rises. For example, employment costs are up 4.2% next year versus the estimated actual for this year.

While there have been increases in the number of teachers (8.6%) and police officers (2.7%), the greatest increase has been in doctors (20.3%). The latter is inexplicable, as the waiting lists have blown out from what they were under the Newman government and ramping is back for ambulances at public hospitals. Queensland already had some of the least efficient hospitals in Australia, and they appear to be getting even less efficient.

Other considerations

GST and Commonwealth Grants Commission

A compounding factor in the government’s projections, and one acknowledged by the Treasurer in a news report today, is future GST distributions. The GST is distributed by the Commonwealth Grants Commission on the basis of ensuring that state governments have enough money to provide a similar level of service to all their citizens.

This principle – Horizontal Fiscal Equalisation – sounds fair enough, but what happens is that state governments who earn more money through mineral royalties, are deemed to have greater earning capacity, and their percentage of the pie is decreased. This led to WA receiving only 30% or so of the GST paid in the state. It also leads to fluctuations in Queensland’s income depending on how much the state earns from minerals.

Given the current royalty boom, next time the grants are assessed, Queensland will be likely to receive less.

To deal with this, the AIP developed a policy that GST should be distributed to the states on the basis of a per capita share. The current system rewards the underperforming states of South Australia and Tasmania, and discourages them from improving, while punishing better performing states like Queensland. This policy has been rejected by the state government, but they should think again. It will be disastrous for state finances when (not if) the GST is cut at the same time as borrowing costs rise as a result of an unfunded splurge on infrastructure.

Privatisation

A similar splurge by Premier Anna Bligh led to the privatisation of rail and port assets. This government has made a virtue out of rejecting privatisation, but so did Anna Bligh’s, until they had a financial crisis. It is almost certain that a future government will need to privatise assets to reduce debt, and this will occur at a later stage in the interest rate cycle when capital assets will be worth much less.

Rather than running-up debt the government should be looking at sales, or long term leases, of some of its assets, such as the Port of Gladstone. Recycling of its huge residential portfolio could also provide much needed capital, at the same time improving life for its social housing tenants.

Adani

With the huge contribution to the state budget of mineral royalties (7.7%), and the government expecting a drop in prices over the course of the budget, it is in the interests of all Queenslanders for the Galilee Basin to be opened-up, which is what Adani’s Carmichael mine will do.

Not that one should put much store in Treasury forecasts of coal prices and activity. The surprise $1 billion improvement in the budget surplus this year was mostly due to Treasury forecasting last year that coal royalties would fall from $3,376,000,000 to $2,750,000,000. Instead they rose to $3,768,000,000.

But of course, before higher royalties are of much use to us, the premier needs to fix the system for distribution of the GST (see above).

Higher interest rates and land tax

There is an inverse relationship between interest rates and property values. As interest rates increase, the value of property tends to go down. This is only mitigated by an increases in rents. Future projections depend on land tax receipts going up by 27.81% over the next three years. This is partly due to a new, higher tax on landholdings over $10 million, but also an anticipation of general property price rises. These won’t necessarily arrive if rates go up, and at the same time, increased rates will make servicing the debt more difficult.

Stranded assets

A significant amount of state debt has been shuffled onto power generation assets. While Queensland’s power generators are phenomenally profitable, due to the disruption to the market caused by unreliable power sources such as wind and sun allowing them to sell at inflated prices, there will be excess capacity, and a need to close some of those power assets, perhaps as soon as 2018/19.

In any event, the state government wants 50% of Queensland’s power to be generated by “renewables” by 2030, which if achieved, would make for less power being sold from coal-fired power stations, even if they kept them all open, and their ability to service and pay back debt would therefore decline, again at a time of probably rising interest rates.

The solutions would be to increase electricity prices, sell the assets while there are buyers, or close them and take the debt back onto the state government’s own balance sheet.

Conclusion

This budget is high risk for future generations. It spends heavily on infrastructure, which will be electorally popular, but does this by taking on excessive debt, at a time when interest rates are due to rise.

The only solutions are privatisations of assets, higher taxes, or more income from sources like mineral royalties. However, the last two bring problems with GST distributions from the Commonwealth, a situation which the Palaszczuck government refuses to address.